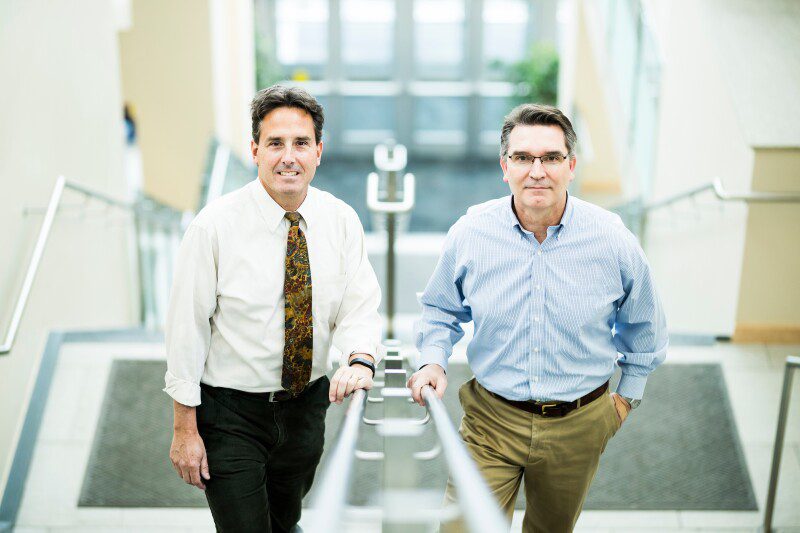

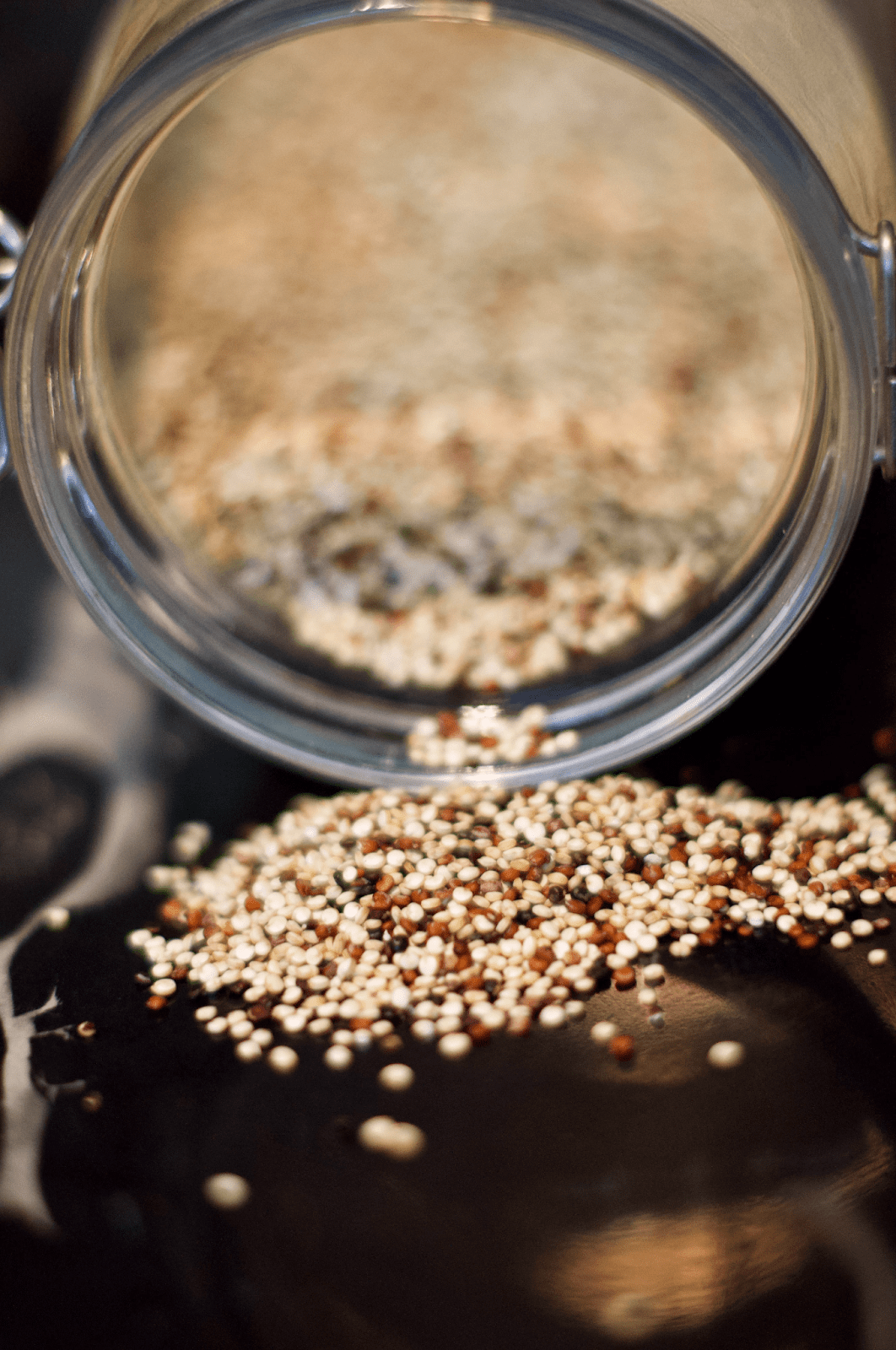

For many, quinoa is another fad-inspired food that snuck into the American culinary melting pot. Yet, the tiny seed represents a world of possibilities for Rick Jellen and Jeff Maughan, plant and wildlife science professors at Brigham Young University (BYU). The two have been working together on a set of quinoa studies that have tremendous applications in everything from botany to fighting global malnutrition.

The diminutive “superfood” is seen as an almost perfect source of nutrition. Maughan explains that “it not only has a full complement of essential amino acids (high protein), but it can be grown in marginal environments—salty soils, dry soils and high altitudes—where other staple crops cannot.” As it currently stands, quinoa is only grown commercially in two countries, Peru and Bolivia, but due to its climate resilience, it has the possibility of being cultivated everywhere.

To tap into the plant’s resilient characteristics, the two professors published a study in 2017 led by KAUST, a Saudi Arabian university, where they fully sequenced the genome of the quinoa plant. They achieved this by sequencing two species from the ancestral gene pool, which enabled the identification of two sub-genomes of quinoa. Using sequencing information, the professors can isolate specific traits in their genetic code and use that information to create strains of quinoa that are better suited for a variety of climate conditions.

Since then, Jellen and Maughan have worked on a project that develops hybrid species of quinoa that are more tolerant to harsh climates, can grow in different soil types and are capable of growing in places where water is scarce. Their research has the possibility to bring better food sources to areas where food insecurity and malnutrition runs rampant.

“When we look at food insecurity around the world, our problem is that we are reliant on maybe just five different plant species,” says Maughan. “What we want to do is increase the number of different plants that we’re utilizing in our diets.”

The project, run by Jellen, Maughan and a team of BYU undergraduate students, is working to implement these optimized strains of quinoa in communities fighting malnutrition or crop failure. The goal is to improve access to a reliable crop or a more nutritious source of protein. The project, which has already been given a grant by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), has identified more than a dozen nations—including Morocco, Mexico, Vietnam, Kenya, and Pakistan—where these strains of quinoa would best be able to take hold. Their team is already working with various institutions to develop and introduce these new strains of quinoa to farmers in Morocco.

Lauren Young, a graduate student at BYU, talks about the situation in Morocco and why this project is so important. “In Morocco, you see a lot of rural people struggling, especially in years where there’s such unpredictable drought,” she says. “Having a crop like quinoa would enable them to have a stable food source where they’re not worrying year to year if they’ll have food on the table every day. It’s hard to hear about the struggles people are having, yet it’s something we can fix.”

While Jellen’s and Maughan’s work won’t completely solve the ongoing food scarcity issue, solutions often start with a simple step. Jellen says, “We are at a crossroads, and we need to have crops that are more reliably productive. That’s why we are so invested in encouraging small farming communities to start growing quinoa.”