(Bloomberg) —

Vodka. Jet fuel. Hand sanitizer. Perfume. A growing number of companies are turning carbon dioxide captured from the air or factory smokestacks into everyday products so the greenhouse gas doesn’t escape into the atmosphere and heat the planet — or at least gets recycled a few times before it does.

Carbon capture technology works by separating CO₂ from other gases using expensive solvents that attract the molecules like iron filings to a magnet. Once captured, the CO₂ can be buried deep underground in places such as depleted oil and gas wells, where it remains for centuries. But that process has its challenges. On top of the high cost, companies also have to figure out how to transport the CO₂ and find the right geological structures in which to store it.

That’s why some startups are turning to what’s known as “carbon capture and utilization” (CCU), where the CO₂ is used to make goods that can be sold to fund the scaling up of their technologies. There’s a potential $1 trillion market in the U.S. alone for products made from captured CO₂ emissions, according to non-governmental organization Carbon180, ranging from plastics and building materials to food and drinks.

One replacement product that can really make a difference in the global effort to reach net-zero emissions is aviation fuel, because there’s currently no fossil fuel-free way to make it.

Dimensional Energy is attempting to make useable fuel from waste carbon and sunlight. Their process works by adding water to captured carbon and heating the mixture to high temperatures using electricity generated from solar panels. Catalysts are introduced that combine the carbon and hydrogen atoms from water into a compound that can be turned into fuel for cargo ships and passenger planes.

“What our process does is it takes what has formally been treated as waste and makes it usable,” Chief Executive Officer Jason Salfi told Bloomberg TV.

The company plans to capture and use its first 500,000 tons of CO₂ by the end of the decade, an extremely ambitious goal. By comparison, the largest carbon-capture plant in operation today — the Orca facility in Iceland run by Climeworks AG — can only capture 4,000 tons of CO₂ a year.

The problem for companies such as Dimensional is that CCU was born as a means of raising funding for carbon capture technologies. But today, with scores of governments and companies setting targets to zero out emissions, there’s been a surge in investor interest in companies that simply capture CO₂ and store it away.

It will always be more effective from a climate perspective to trap captured CO₂ underground than attempt to use it again, according to Howard Herzog, a senior research engineer at the MIT Energy Initiative. Turning the gas into something else requires energy and it’s not always easy to get that from completely renewable sources, including hydrogen. That limits the ability of these processes to have a meaningful climate impact, especially when there are other ways to cut emissions from most of these products, he said.

While it can be an effective marketing tool, experts say in most cases there’s no need to replace everyday goods with versions made from captured carbon. When it comes to things like alcoholic drinks and hand sanitizer, they’re at best an educational tool for the benefits of investing in carbon-capture technology and at worst a gimmick that doesn’t do the planet much good.

Brooklyn-based Air Company, for example, says it’s created the “most sustainable alcohol in the world” by mixing captured CO₂ with hydrogen made from water and wind power. Their spirits can be turned into a variety of consumer goods, including vodka, which starts at $65 a bottle.

“Using the same area of land, our technology absorbs CO₂ at around 100 times the rate of a well-curated forest” said Air Company Co-Founder Gregory Constantine.

Several other companies are aiming key to replace a plethora of basic goods.

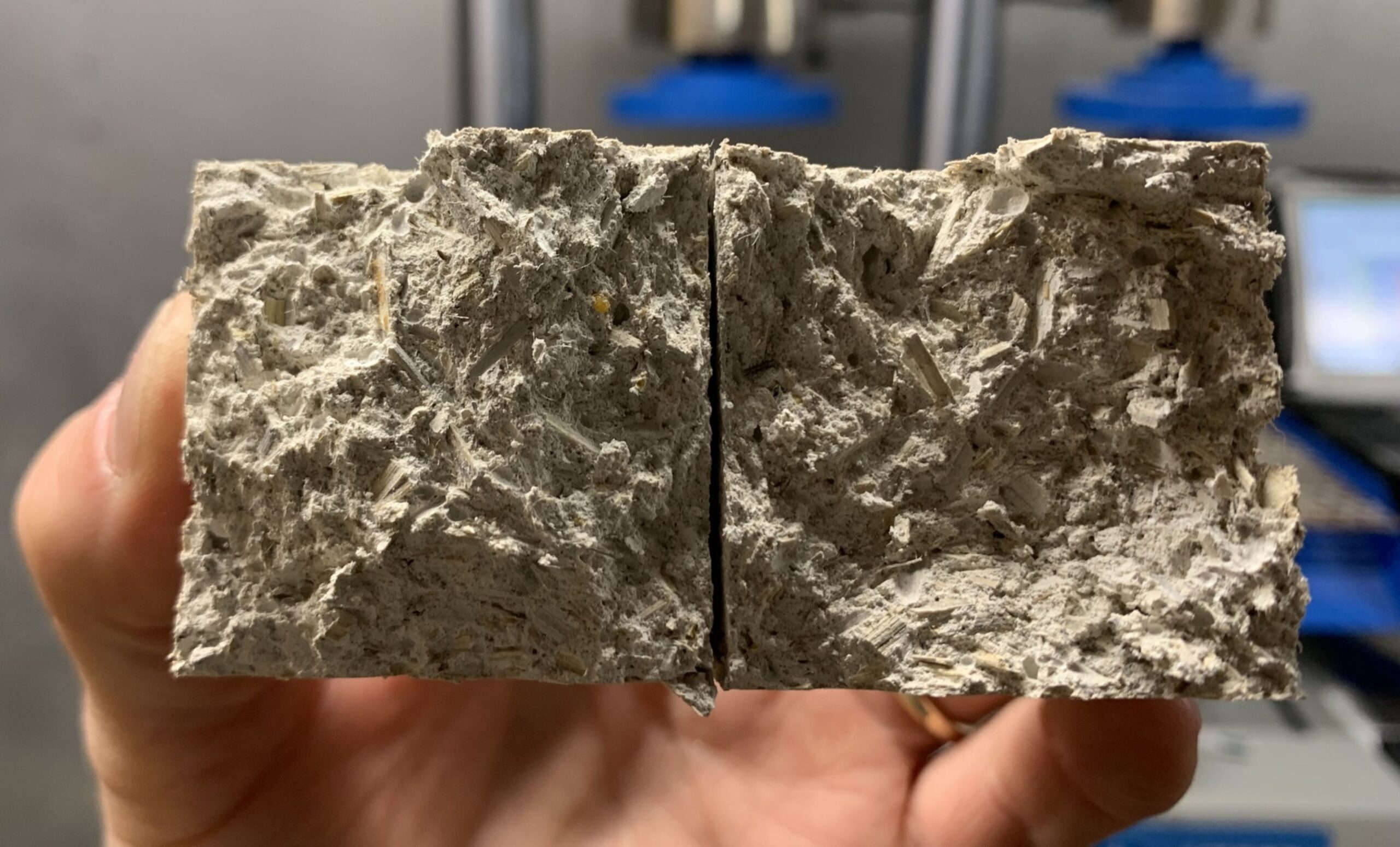

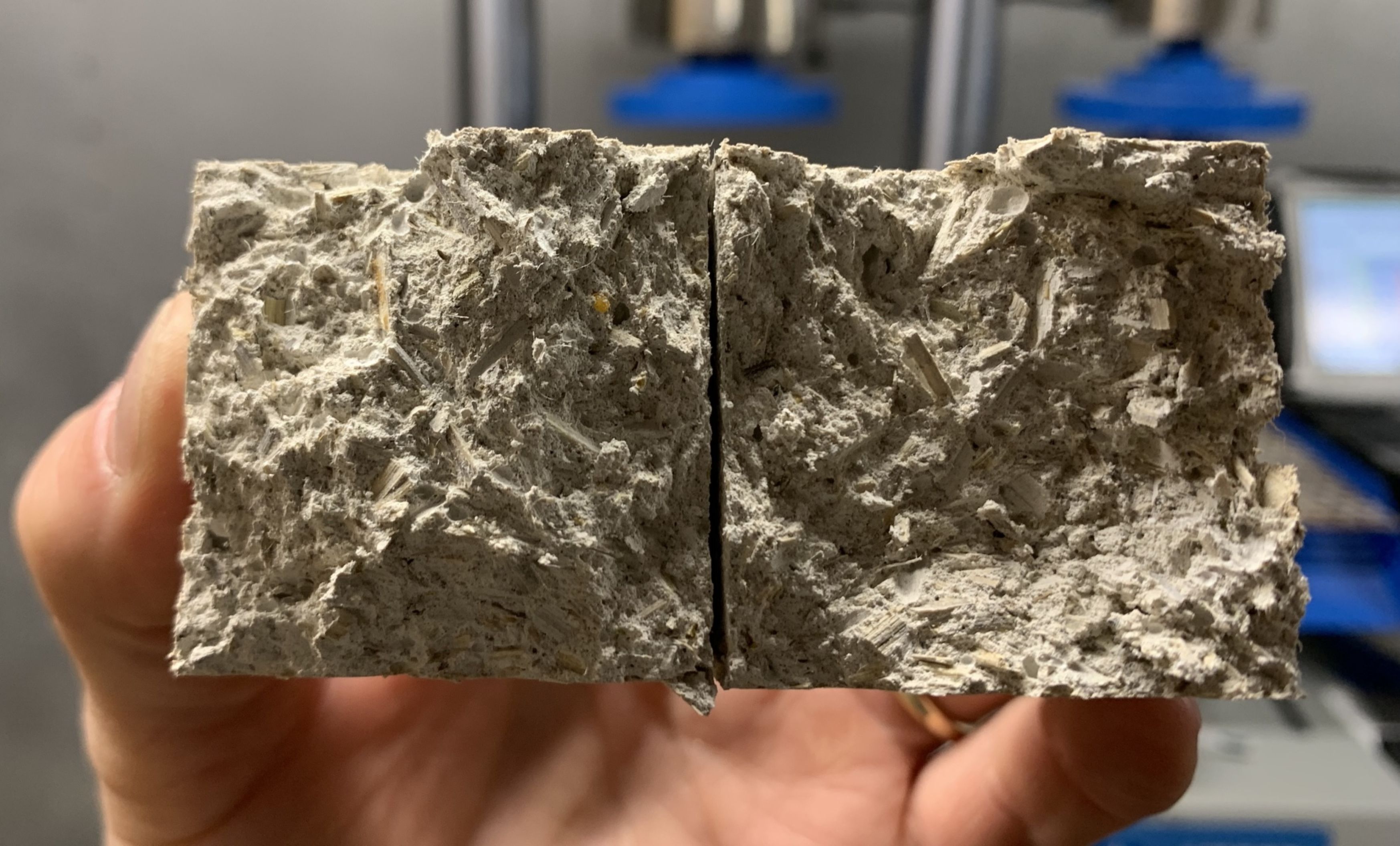

U.K. startup Adaptavate has created drywall that uses agricultural waste and a lime-based binder that captures CO₂. If its product ends up being widely used, it could cut emissions from the global building sector, which was responsible for as much as 38% of global energy-related emissions in 2019.

Econic Technologies, founded at Imperial College London in 2012, has developed technology that uses captured CO₂ to make polymers that are the starting point for a range of consumer and industrial products. Econic’s catalyst and process, which it licenses to manufacturers, can replace as much as 50% of traditional oil-based raw materials, according to Chief Executive Officer Keith Wiggins.

The company wants to substitute polyurethane, a polymer that’s used to make foams that are found in insulation, mattresses, fridges to coatings and adhesives. Econic announced a co-production partnership with India’s Manali Petrochemicals last year and says that if all polyurethane worldwide was made with their technology, more than 11 million tons of CO₂ emissions would be avoided.

But a study published in the journal Nature in 2017 was less optimistic about the potential of how big CCU can get. The researchers concluded that even if there was enough clean energy available to support large-scale CCU, the actual contribution of the sector to reaching net-zero globally would be negligible, at less than 1%, making it a costly distraction.

“Carbon utilization has advantages as a climate solution,” said Giana Amador, policy director at Carbon180, but it doesn’t permanently eliminate carbon from the atmosphere. “Neither carbon capture nor carbon removal is a license for fossil fuel companies to continue emitting,” she said.(Corrects location of Orca facility in seventh paragraph.)

To contact the authors of this story:

Sylvia Klimaki in London at sklimaki@bloomberg.net

Ryan Hesketh in London at rhesketh3@bloomberg.net

© 2022 Bloomberg L.P.