The American decarbonization strategy has placed a hefty bet on renewable energy. Solar and wind are deploying at an accelerated pace, but it takes a lot of solar panels and wind turbines to make up for what fossil fuels can generate. Hydrogen is considered one of the highest-performing renewable energy sources, but how far has American hydrogen energy production advanced?

The Business Download spoke to two hydrogen energy experts who advocate from two different organizations. Kathleen Biggins is the president and founder of C-Change Conversations, a non-partisan climate change think tank. Mothusi Pahl is vice president of business development and government affairs at Modern Hydrogen, a low-cost hydrogen solutions firm. Each provides a unique perspective that encapsulates how far the sector has come but also stresses more work is needed.

Both explained that green hydrogen is made with renewables. The problem is scaling renewables to the point where they can be the sole power source for electrolysis.

When asked how hydrogen — especially green hydrogen — would out-compete natural gas, Biggins explained, “To compete with natural gas and grey hydrogen, green hydrogen first needs a very large supply of wind and solar to drive the low price and excess supply to high price and short supply cycle outlined above.”

“Policies (such as a price on carbon or clean electricity standards) to make natural gas less economic than green hydrogen are probably also needed and would also help accelerate wind and solar deployment,” she continued.

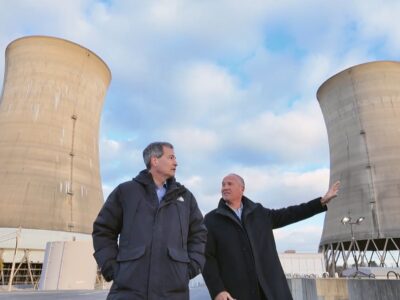

Photo Courtesy Shaun Dakin

We will likely see more hydrogen-generated electricity integrated with other renewable energy sources. When the wind or sun isn’t strong enough, hydrogen will make up the difference. Pricing remains an issue, though, Biggins said.

“Further ‘hydrogen power’ — that is, hydrogen-generated electricity — will be used almost entirely only during periods when wind and sunshine are largely unavailable,” Biggins said.

“This is because, when the grid has large amounts of wind and solar power generators, power prices will be very low when wind and sunshine are fully available (because the total grid supply, including the full output of wind and solar, would exceed the total demand).”

“But power prices will be very high when wind and sunshine are both largely unavailable (because without wind and solar generation, total supply could well be less than demand),” she continued.

Hydrogen energy will be stored and used during high power pricing periods, especially when solar and wind aren’t at maximum capacity. This strategy is ideal because it will make green hydrogen profitable and allow it to serve as an excess energy source.

“There is no competition between them; instead, there are real synergies,” Biggins said. “These synergies don’t exist for grey hydrogen or natural gas, which are the real competition that green hydrogen must overcome to be successful in filling in the gaps in wind and solar electricity production.”

Pahl offered another perspective on the progress of the hydrogen energy sector.

“If you zoom out on the objective here, the argument for green hydrogen should be about decarbonization as the objective and reducing your CO2 footprint,” Pahl said passionately via a Teams call. “It should not be about the pathway by which you reduce it. It means what’s the most cost-effective and environmentally sound method of reaching decarbonization.”

“There are a lot of rate-limiting steps around getting hydrogen adopted in general, but very specific to any hydrogen process that requires electricity,” he continued. “It means that you need to have an electrical grid in place that can support it. It means that you need to have power generation capacity in place that can support it. And that is not a foregone conclusion.”

He said decarbonization focuses on three categories: pollution from mobility, pollution from electricity generation, and pollution from heating.

All rely on hydrocarbons in some form, and while implementing renewables is a great idea to decarbonize, it is expensive and takes time.

“I am a huge champion for renewables, and we’re currently not investing enough in renewables,” Pahl stressed. “We’re not moving fast enough. We need more renewables, but we can’t wait for decarbonization.”

The hydrogen production sector still relies on sources like natural gas to produce at a large enough scale to use commercially. Pahl believes that we won’t have 100% renewable energy generation for electricity and heating in the next two decades; however, that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t strive for it.

“We’ve got to decarbonize faster, which means we’ve got to go to the core of the hydrocarbon beast, where the emissions are the worst,” he said. “And that’s a lot of industrial operations, a lot of mobility-related issues, which means let’s get hydrogen on the market in the most economical and most cost-effective, the lowest carbon intensity pathways possible. We understand a portfolio of approaches that can decarbonize and deliver hydrogen to the point where it’s needed at a lower carbon intensity score than green hydrogen.”

Photo Courtesy Joshua Sukoff

Politics also remains a challenge to further progress in hydrogen deployment. While advocating for renewable energy is great, said Pahl, he stresses that a multi-faceted approach is needed to decarbonize transportation, heating, and electricity.

When asked whether hydrogen fuel-cell vehicles will ever become mainstream, Pahl said, “I don’t think there’s a long-term pathway for hydrogen cars, and that’s because electrification of passenger vehicles is a way more efficient option than hydrogen generation.

That, however, does not scale up to heavy-duty vehicles. Batteries don’t work for heavy-duty vehicles. If you take up 50–75% of your carrying capacity with batteries, you’ve defeated the point of a heavy-duty view.”

“I think that hydrogen-powered vehicles and hydrogen fuel cells are the most likely pathway due to their efficiency, the time it takes to recharge a battery versus the time it takes to refuel hydrogen vehicles, and the capacity that remains for heavy-duty work when you’re not fulfilling up your transport bay with batteries,” he continued.

Pahl said residential hydrogen use is also a long way from happening. There is a lot of red tape to navigate, so it will likely be mandated by local or state governments. It would also be costly and wouldn’t necessarily solve the carbon emission problems. The industrial and commercial sectors are still the heaviest polluters and consumers of fossil fuels.