It was 3 p.m. on Sept. 4, 1882, on Pearl Street in Manhattan, when Thomas Edison launched the nation’s first central power plant and local grid with about 80 customers. Edison was a proponent of the direct current (DC) system, in which power goes one way and could connect systems of different frequencies.

It eventually lost out to George Westinghouse and Nikola Tesla’s alternating current (AC) system, where power can flow both ways, reversing its direction in intervals. Although AC has to overcome the more difficult hurdle of requiring generators with the same frequencies, it was better at transporting high voltages further.

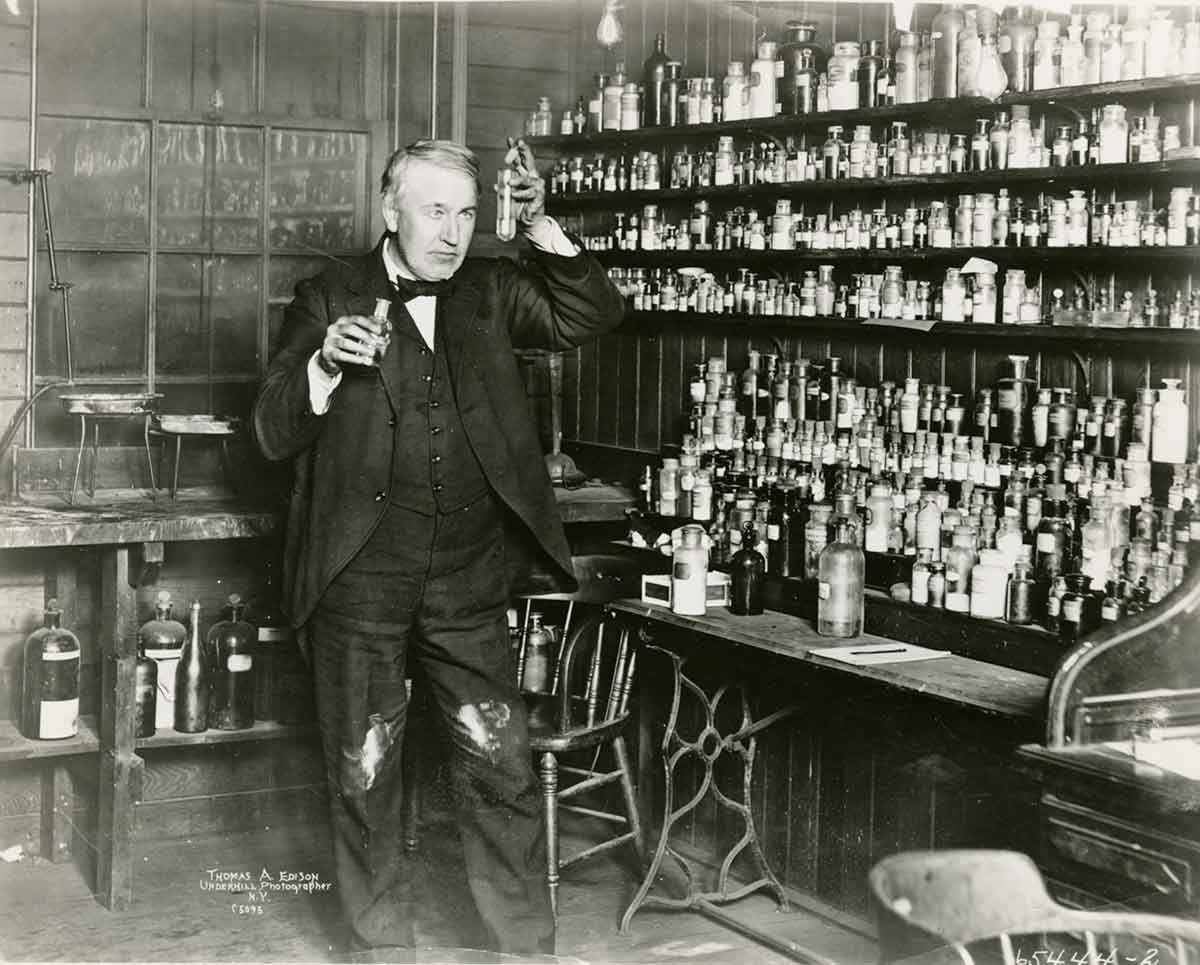

Photo Courtesy ConEdison

It was not until the end of the “Roaring ‘20s” that most cities in the country had electricity, and rural areas only started to catch up with President Franklin Roosevelt’s creation of the Rural Electrification Administration and the passage of the Rural Electrification Act in the 1930s. There was, after all, the obvious expense of building the required infrastructure to consider. As a result, the power system was considered a “natural monopoly,” and states granted utility monopolies.

As grids grew, they needed to be managed to preserve stability, with supply meeting demand for every second of every day so that blackouts did not occur from an undersupply and energy did not get wasted from an oversupply. Utility companies were also responsible for being grid operators or balancing authorities that consistently predicted and monitored to ensure supply met demand. They could source power from other areas, shut off some people’s power, or turn off entire generators altogether.

Photo Courtesy ConEdison

However, to lower the cost of energy in the face of the 1970s energy crisis, Congress decided to allow for more competition via the 1978 National Energy Act, one part of which allowed companies that were not utilities to enter a wholesale market for power generation, where those who could deliver cheaper electricity won.

1992’s Energy Policy Act went even further by allowing companies that were not utilities to compete in transmission networks.

Further deregulation or “restructuring” and movement away from the old monopoly system has been the name of the game for many states but not all.

It is important to note that the government still very much has its hand in the energy markets. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) is the agency that regulates interstate transmission on the Eastern and Western Interconnections and wholesale transactions between regional operators. Meanwhile, the North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC) combats any risk facing the grid by developing reliability standards and monitoring that reliability.

Alongside NERC, six regional entities — the Northeast Power Coordinating Council, ReliabilityFirst, SERC Reliability Corporation, Midwest Reliability Organization, Texas Reliability Entity, and Western Electricity Coordinating Council — are in charge of enforcing those standards, covering both regulated and deregulated states. Together, NERC and the regional entities form the ERO Enterprise. Finally, states maintain oversight of the retail price of power.

Photo Courtesy Federal Energy Regulatory Commission

As we zoom in further, there are differences between states that decided to restructure and those that did not. In restructured, deregulated states, customers can select their electricity supplier, shopping around for the best price from a large swath of suppliers. Therefore, FERC ordered the creation of transmission system operators — taking the form of either regional transmission organizations (RTOs) or independent system operators (ISOs) — that could oversee inter-state or large generation and transmission networks.

Rather than generating their own electricity, the RTOs/ISOs maintain oversight of the wholesale markets, ensuring non-discriminatory access by independent suppliers.

They also act as balancing authorities in making sure supply and demand match and approving project connections to the grid.

There are currently seven RTOs/ISOs in the US — ISO New England, New York ISO, PJM Interconnection, Midcontinent ISO, Southwest Power Pool, California ISO, and the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT) — plus two in Canada. Notably, in managing the Texas Interconnected System, ERCOT is not only the sole RTO/ISO not regulated by FERC, but it is also the only place in the country where the major interconnection, RTO/ISO, and balancing authority are all the same system.

Photo Courtesy Electric Reliability Council of Texas

In regulated states that did not restructure, accounting for one-third of U.S. power demand and located primarily in the West and Southeast, vertical integration remains. Utilities generate and balance electricity and own all three aspects of the grid, and consumers only buy power from the one that has a monopoly in their location.

However, state and local governments have maintained oversight of in-state construction and power distribution. State Public Utility Commissions (PUCs), Public Service Commissions (PSCs), or Utility Regulatory Commissions (URCs) oversee all three aspects of the grid. They approve the construction of new generating facilities and transmission and distribution lines after requiring utilities to go through an integrated resource planning (IRP) process to show why the investment is essential and how it will be used to meet demand.

They also affirm the retail prices that each power company can charge for distribution, allowing them to recuperate their investments and earn a fair rate of return but with a keen eye out to prevent overcharging. In deregulated states, in contrast, the PUCs only oversee distribution, while RTOs/ISOs maintain control over generation and transmission.

The federal government has also taken a significant role in investing in and promoting grid infrastructure, which we will explore in part three.