(Bloomberg Businessweek) —

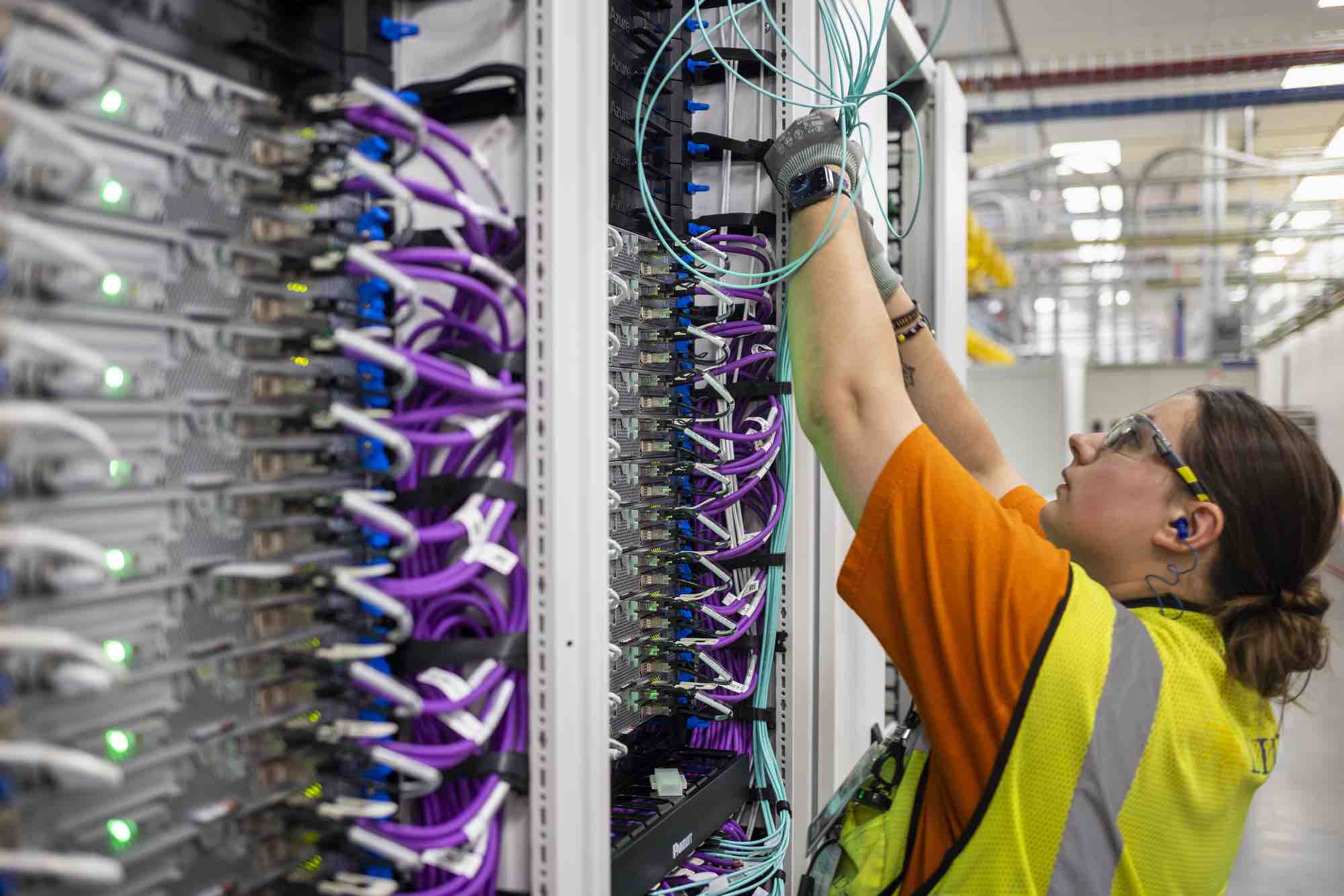

The semiconductors whose components are measured in nanometers are the marvel of modern artificial intelligence data centers, but some of the most important machines in such facilities are the fans. Without cool air constantly blowing through the racks of computers, the advanced chips would cook themselves. The cost of running enough fans and air conditioners to keep this from happening is leading chipmakers and data center operators to find completely different ways to do things.

Such aspirations were on display on Nov. 15, when Microsoft Corp. announced its first major foray into advanced chipmaking for AI. Its new Maia 100 chip, intended to compete with Nvidia Corp.’s top-line products, is designed to be attached to a so-called cold plate, a metal device that’s kept cool by liquid flowing beneath its surface. The technique could be an intermediary step to full-immersion cooling, where entire racks of servers operate inside tanks of specialized liquid.

People who have to worry about cooling computer servers have known about the advantages of liquid cooling for years—water has about four times the capacity of air to absorb heat. Some crypto miners have experimented with the technique, and there are data centers already adapting cold plate technology to chips that have been designed for standard air cooling. Hardcore gamers looking to squeeze performance out of their PC rigs—and to cut down on the maddening whir of high-powered fans—show off their custom-built cooling systems, featuring illuminated water pipes.

But liquid cooling has its drawbacks. Water conducts electricity and can ruin expensive equipment, requiring alternative fluids if they have to come into direct contact with computers. For many large data centers, implementing a whole new cooling strategy would be a massive infrastructure project. Operators would have to worry, for instance, about how to keep the floors from collapsing under the weight of all the liquid needed to submerge rows of seven-foot-high computer cabinets. This has led major data center operators to stay the course with fans, leaving liquid cooling techniques to the tinkerers.

The massive computing requirements of AI are changing the equation. Advances that increase a chip’s capacity multiply the amount of electricity it needs; the more power it uses, the more heat it generates. Each Nvidia H100 AI accelerator, the gold standard for AI development, uses at least 300 watts of power—about three times the amount of a 65-inch flatscreen television. A data center may use hundreds or even thousands of the processors, each one costing more than a family car.

Cooling is the fastest-growing physical infrastructure cost for data centers, with a 16% compound annual growth rate, according to a November 2023 report by Omdia Research. As much as 40% of the overall power used by a data center goes to cooling, says Jennifer Huffstetler, a product sustainability executive at Intel Corp. “Power is the No. 1 limiter for data centers,” she says. Challenges related to cooling are causing some of them to cut back on certain types of components, leave space between the racks empty or throttle down expensive chips to keep them from overheating.

Microsoft’s Maia chips are designed to operate alongside large coolers which circulate liquid through cold plates connected directly to them. This allows the chips to operate in standard data centers, and Microsoft says it will start installing them in 2024. Eventually, Microsoft’s Azure cloud division hopes to make liquid cooling a much larger part of all its data center operations, according to Mark Russinovich, Azure’s chief technical officer. “It’s proven technology, in production,” he says, sitting in his home office. “It’s been in production for a long time, including sitting here under my desk on my gaming PC.”

Over the next few years, Microsoft also plans to develop data centers that can accommodate immersion cooling, where racks will operate from inside cooling baths. This would be more efficient than cold plates, but it also requires a broad examination of equipment at every level.

One tricky question with immersion cooling is what type of liquid to use. Previous experiments have used so-called forever chemicals, polyfluoroalkyl substances that don’t break down naturally. Safety concerns and environmental regulations are leading to the reduced use of these chemicals; 3M, a major manufacturer, said in late 2022 that it would stop making them.

Microsoft hasn’t said what liquid its systems will use. Shell PLC, the energy company, has developed a process that converts natural gas to synthetic liquids, and Intel has said it’s testing them.

Other major chipmakers’ plans for liquid cooling remain unclear. Intel has recently changed its policies to allow its customers to build their own liquid cooling systems to cool certain Intel products without voiding their warranties, says Huffstetler.

A fundamental overhaul may be necessary to have data centers keep up with the requirements of advancing AI systems. Finding places to put the facilities is already becoming more challenging, as some communities push back against accepting an energy-hungry plant that provides few job opportunities.

It’s possible that liquid cooling could make AI a better neighbor, though, by becoming a source of warm water. Jon Lin of Equinix, the largest provider of outsourced data centers, is one operator that’s already begun to implement cold plate cooling. He says the company will use the outflow of water from one of its facilities in Paris to heat the pools during the 2024 Olympics. —With Dina Bass

To contact the author of this story:

Ian King in San Francisco at ianking@bloomberg.net

© 2024 Bloomberg L.P.