(Bloomberg Businessweek) —

Loop Mission takes an unconventional approach to the way it makes snacks—and money. The startup pays for produce that would otherwise be discarded and gives it a second life in juices, sodas, beers, soaps, and cookies, which are priced as low as possible to hasten sales and move inventory. The formula is designed to help the planet and turn a profit.

The Canadian company is tackling food waste, a major contributor to climate change, by creating a market for surplus fruit and vegetables while tapping into a growing consumer ethos of sustainability. Its products are sold across the nation at major supermarkets and alcohol vendors, and Loop—the name reflects its focus on the circular economy—is preparing to enter the U.S.

“You can’t just be a hippie trying to save the world,” co-founder David Côté, 39, says at Loop’s airy loft-style headquarters in Montreal. “You need to be in the corporate world to change those big companies out there.”

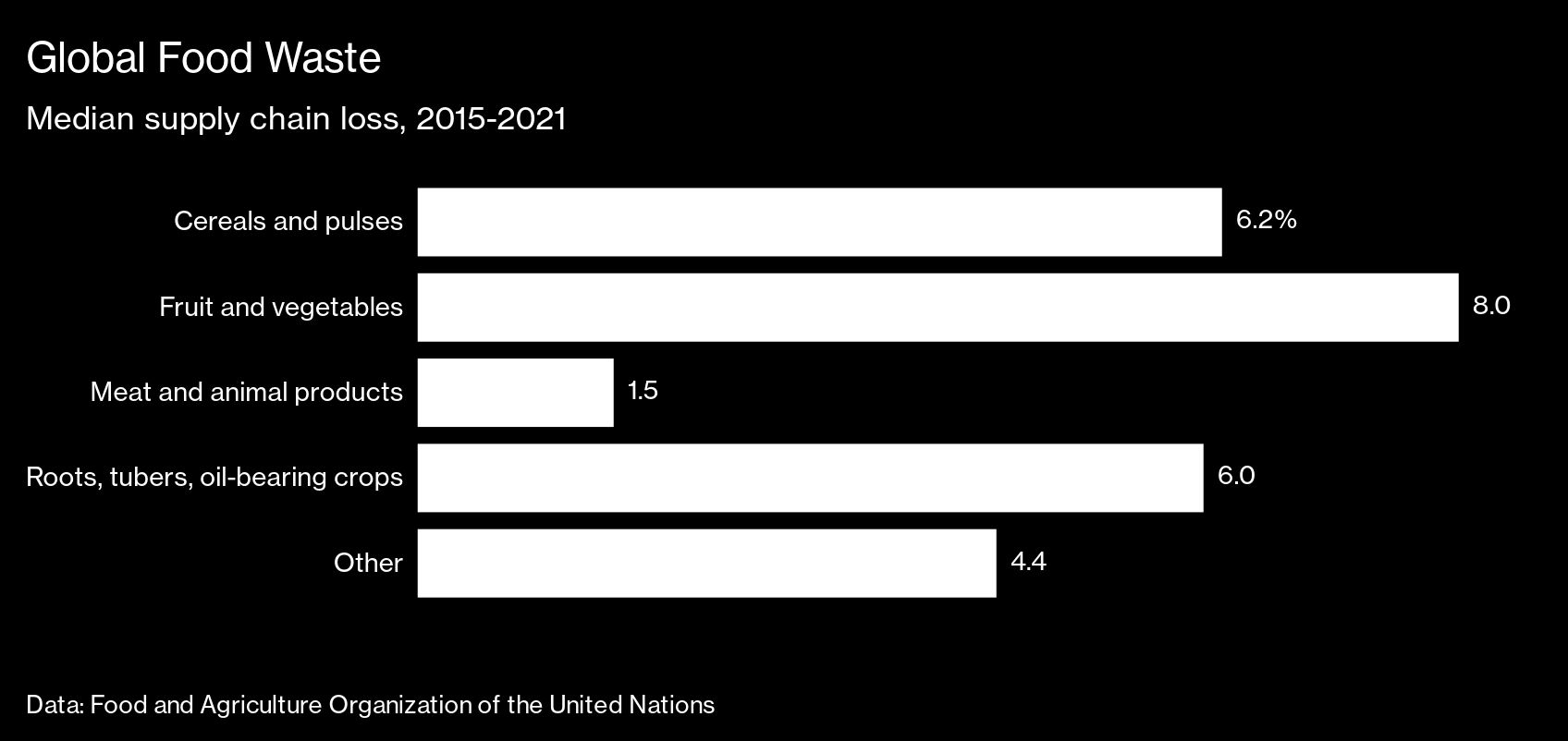

Despite rampant food insecurity, 14% of food harvested worldwide never gets eaten, according to a 2021 report by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. Much of it ends up in the trash, generating enormous quantities of methane. Between 8% and 10% of annual greenhouse gases come from food in landfills, according to the UN Environment Programme.

Most of this food isn’t rotten. Grocery stores won’t let shelves go bare, and consumers shun produce with blemishes, so retailers order too much. Meanwhile, there’s little slack in the distribution chain: If a shipment of produce arrives at a warehouse even a few days later than expected, it might as well be rotten. “We get phone calls every day about truckloads of stuff being wasted,” Côté says. Five years in, Loop says the amount of excess food it’s transformed includes more than 8,000 metric tons of produce.

The company, legally registered as Loop Juices Inc., is part of a small but growing number of companies focused on upcycling food waste. Some transform spent grain from beer-brewing into pasta flour, make powdered tea from arabica coffee plant leaves, repurpose “ugly” fruit into dried snacks, and purify and bottle leftover water from juicemaking.

A chef and self-professed “health freak,” Côté is a native French speaker who talks a mile a minute in English as he recounts Loop’s origin story, pausing only to down one of his Deep Green smoothies. In 2015 he was at loose ends. The entrepreneur had a chain of raw vegan restaurants and a kombucha company, together employing 120 people, and felt like he’d accomplished his life’s work by bringing plant-based meals and fermented teas to the masses.

Then he met Julie Poitras-Saulnier—now his wife and Loop co-founder—on a Ferris wheel at a networking event. Trained in environmental sustainability, she was also looking for a new challenge. As they went round and round, Côté told her about a call he’d received from a produce distributor in Quebec who was discarding 16 to 25 metric tons of fruit and vegetables—every day. He recounted going to the warehouse and encountering a wall of produce—35 skids’ worth—destined for the trash. The trays of perfectly ripe mangos gave him the chills.

Poitras-Saulnier was captivated by the story and agreed to work with Côté to do something about it. She sold her house, he sold his businesses, and they moved in together, soon creating four cold-pressed juice recipes in their kitchen using the distributor’s produce. Stuffed with pineapple, turmeric, cantaloupe, beets, kale, and other premium ingredients, the juice was on store shelves less than a year later, selling for C$4.99 ($3.94) a bottle, about half the price of the juices they drank each day. Initially, their recipes were based on produce they knew they could regularly acquire. Later, they added new and one-off products based on what became available.

Large food manufacturers, farmers, and grocery stores reached out for help managing surplus produce. The couple started making probiotic sodas, sour beer from old bread, gin from potato peelings, and soap from fast-food joints’ leftover deep-fryer oil. “We put juice in everything. We put juice in our beer, we put juice in our gin, we put juice in our soaps, we put juice in our sodas,” Côté says.

Marketing was tricky: The key was stressing that the produce, while unloved (and sometimes a little ugly) was still high-quality. They paid suppliers 30% to 40% of the food’s original value—even though it typically costs retailers to get rid of waste—reasoning that putting a price on something thought to be a worthless liability was key to building a sustainable market.

To date, Côté and Poitras-Saulnier have created 33 marketable products together—and a baby daughter. Côté, whose tongue-in-cheek business card says “superhero,” is mulling a line of baby food, and the company is about to launch fruit-pulp cookies. He typically has 15 recipes in the works at one time, of which only two or three will end up in production.

Poitras-Saulnier, 34, the chief executive officer of the venture, is focused on a new business-to-business division, Loop Synergies, which the duo recently created to consult with grocery stores and manufacturers looking for ways to upcycle their own excess ingredients. She and Côté also look for ways to extend the life of produce they don’t have the capacity to immediately transform into juice or soda, by creating purees and dehydrated powders they can supply to other food manufacturers as a sustainable ingredient.

To prevent manufacturers from using Loop ingredients for greenwashing—for example by adding an insignificant amount of their products to something and calling it sustainable—Poitras-Saulnier is working on a labeling strategy so companies using their ingredients must reach a certain threshold of upcycled content before being associated with the brand. She’s also planning a detailed environmental audit of the emissions tied to every aspect of the business. Right now, Loop’s factory is on the same site as its main supplier— Courchesne Larose Ltd., the distributor that first approached Côté. For anything the company trucks in, it ensures the carbon footprint of the travel is offset by upcycling the items it’s saving from the trash.

Loop plans to open a second factory in a couple of months outside Montreal, funded in large part by Courchesne Larose. And it’s just signed an agreement to sell its products in the U.S., with the Phoenix-based chain Sprouts Farmers Market Inc. An expansion into Europe may follow. The new factory will help the company move toward profitability. So far, it’s funneled its proceeds into expansion, Poitras-Saulnier says. Last year, Loop broke even; an initial public offering could one day be in the cards, she says.

In the meantime, Loop is still turning away 200 metric tons of food a week, Côté says. And so the couple will keep adding products to soak up that supply of excess food, while they try to educate businesses that sustainability can create value rather than just add to costs. “Our vision,” he says, “is to be in every single aisle of the grocery store, worldwide.”

Read next: Oreo Maker Mondelēz Says Covid Couldn’t Quash World’s Snacking Habit

To contact the author of this story:

Danielle Bochove in Toronto at dbochove1@bloomberg.net

© 2022 Bloomberg L.P.